Monitoring new syscalls with Falco

Falco is currently the de facto standard for runtime threat detection in Kubernetes environments. The project is growing at a very fast pace, and so is its open source community. The role of Falco is to collect all the system events of a cluster and send some kind of alert whenever suspicious behavior is detected. Among the other data sources supported, system calls are the core kind of events monitored by Falco.

Unfortunately, the set of supported syscalls changes from time to time as new versions of the Linux kernel gets released, and Falco needs to be updated accordingly. There are still a bunch of syscalls that are yet not supported by Falco and its libraries. As such, an attacker could potentially compose malicious software that relies on some of these unmonitored syscalls as a means to bypass Falco's security. This is a known issue and has first been reported during this talk by maintainer Leo Di Donato.

Hence, there is a great opportunity in contributing to the project by adding support to some of the missing syscalls. Some of them provide brand new functionalities, whereas others are new alternative versions of already existing syscalls.

In this post, we share our experience of implementing the support to openat2, which was still missing from the list. We decided to start by adding this syscall as we thought it could be meaningful for the security monitoring purposes of Falco. We have documented our development process step by step, by sharing our thoughts and by providing some context about the parts involved.

The complete source code of this project can be found in the pull request we recently opened.

The New Syscall

The openat2 syscall is a recently introduced alternative to the already existing openat, created to extend its capabilities and to enhance control and configurability.

// https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man2/openat2.2.html

long syscall(SYS_openat2, int dirfd, const char *pathname,

struct open_how *how, size_t size);

The purpose of this syscall is to open a file in a given path or to try creating it if it does not exist. A rich set of flags can control the behavior of this action, and a new data structure open_how has been introduced to be extended in the future in case new configuration flags will be needed. This syscall appeared in the Linux kernel starting from version 5.6, so we can assume it is supported only in the most up-to-date production environments.

In theory, the Falco monitoring can potentially be bypassed by using openat2 instead of openat. If malicious software is carefully built to only use openat2, Falco would not be able to detect anomalies related to file opening, thus weakening its security guarantees.

Nonetheless, we found this syscall relatively easy to implement in Falco, because the code that supports openat was already at our disposal.

Architectural Overview of Falco

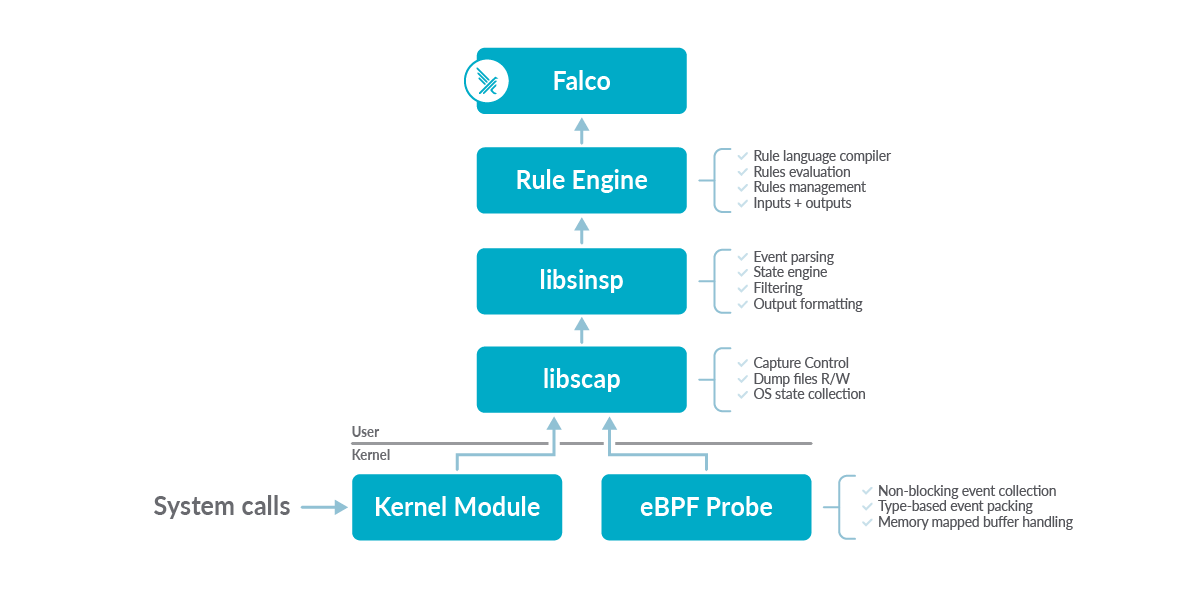

Having a high-level understanding of the architecture of Falco is the key to identifying which part of the project needs to be updated while adding a new syscall. On the other hand, we also learned a lot about the Falco codebase while trying to add openat2. The picture below provides an overview of the bottom-up architecture of the project.

On the bottom, there are the Kernel Module and the eBPF Probe, which are often simply called drivers. The Kernel Module offers slightly better performance and compatibility, whereas the eBPF probe is optimal in terms of security and modernity.

The two drivers are equal in functionality and run in the kernel space to catch internal events (such as syscalls) and then push them up to the userspace. Then, libscap consumes each event and enriches them with some context information. This component can also read and write dump files. The next in line is libsinsp. This is where each event is parsed, inspected, and is evaluated against a set of user-specified filters.

Finally, Falco and its Rule Engine consume the processed events, orchestrate the behavior of the underlying libraries, and send the output alerts to the outside world. However, the core logic responsible for processing each system call is contained in the low-level drivers (kmod and eBPF) and the userspace libraries.

Adding OS-Independent Representations

The first thing to pay attention to is to make sure that Falco is as independent as possible from specific versions of the Linux kernel or specific platforms. This is attained by creating internal representations and definitions of all the values that are expected to vary across different systems. Most of those definitions are part of the codebase of the drivers, so that's the part that we looked at first.

Event and Syscall List

First, we noticed the presence of an enumeration representing all the possible system events that are captured at the driver level. This includes syscalls too, among some other event types. We proceeded by adding constants for openat2.

// driver/ppm_events_public.h

enum ppm_event_type {

// ...

PPME_SYSCALL_OPENAT2_E = 326,

PPME_SYSCALL_OPENAT2_X = 327,

PPM_EVENT_MAX = 328

};

Most careful readers will notice that we defined two constants for the same syscall. This is mandatory since the Enter and the eXit of a syscall are seen as two distinct events. Most of the time, the interesting one is the exit event because it carries both the syscall arguments and the return value, but there is a value in the enter event for many use cases too.

There is also an additional enumeration that defines syscalls specifically. This is the abstract representation of syscalls numbers used internally by the engine.

// driver/ppm_events_public.h

enum ppm_syscall_code {

// ...

PPM_SC_OPENAT2 = 322,

PPM_SC_MAX = 323,

};

Last but not least, don't forget to bump PPM_EVENT_MAX and PPM_SC_MAX values too!

Finally, we noticed that the drivers provide support to the ia32 architecture by maintaining a wide set of definitions. In many cases, some enumerations and definitions are replicated with the _ia32 prefix. At this point, we redefine the actual syscall number of openat2 for ia32.

// driver/ppm_compat_unistd_32.h

// ...

#define __NR_ia32_openat2 351

// ...

#define NR_ia32_syscalls 352

// ...

Again, remember to increment NR_ia32_syscalls value too!

Argument Flags (optional)

In many cases, the syscall arguments include a flag value in which each bit represents a given configuration option. All those options are usually defined as constants, and we need to provide an internal representation for them too. This step is theoretically optional because each syscall varies case by case. In the case of openat2, we re-defined the options of the resolve flag field inside the open_how struct argument.

// driver/ppm_events_public.h

#define PPM_RESOLVE_BENEATH (1 << 0)

#define PPM_RESOLVE_IN_ROOT (1 << 1)

#define PPM_RESOLVE_NO_MAGICLINKS (1 << 2)

#define PPM_RESOLVE_NO_SYMLINKS (1 << 3)

#define PPM_RESOLVE_NO_XDEV (1 << 4)

#define PPM_RESOLVE_CACHED (1 << 5)

// ...

extern const struct ppm_name_value openat2_flags[];

Accordingly, it's also necessary to create a table containing the textual representations of the flag options. These are usually used for formatting the output alerts of Falco.

// driver/flags_table.c

const struct ppm_name_value openat2_flags[] = {

{"RESOLVE_BENEATH", PPM_RESOLVE_BENEATH},

{"RESOLVE_IN_ROOT", PPM_RESOLVE_IN_ROOT},

{"RESOLVE_NO_MAGICLINKS", PPM_RESOLVE_NO_MAGICLINKS},

{"RESOLVE_NO_SYMLINKS", PPM_RESOLVE_NO_SYMLINKS},

{"RESOLVE_NO_XDEV", PPM_RESOLVE_NO_XDEV},

{"RESOLVE_CACHED", PPM_RESOLVE_CACHED},

{0, 0},

};

Quite straightforward so far, uh? Lastly, we needed to create a mapping function that will be invoked by the drivers to convert the flags in the internal representation format:

static __always_inline u32 openat2_resolve_to_scap(unsigned long flags)

{

u32 res = 0;

#ifdef RESOLVE_NO_XDEV

if (flags & RESOLVE_NO_XDEV)

res |= PPM_RESOLVE_NO_XDEV;

#endif

// Repeat for all the flags options...

return res;

}

Using ifdefs here is a good practice to avoid compilation issues that may arise on different platforms. Generally, this could be a good practice to make the compilation step as robust as possible, given the fact that openat2 is not yet supported in many kernel versions and standard libraries.

Tables

We proceeded in our implementation by modifying the information records that Falco maintains for each event type. These tables are used by both the drivers and libscap, and define a sort of contract describing the event data stream pushed from the kernel.

Starting from g_event_info, we must fill in the name of the syscall, its category, flags, and all of its arguments. As always, a good rule of thumb is to find a similar syscall already supported to see how it is handled to better understand patterns and good practices. By working on this table, you will surely notice the presence of multiple versions of the same syscall. execve and openat2 are good examples of this phenomenon. The reason is that, in old code revisions, a new version of the same syscall needed to be added every time its signature was changed in the kernel, most probably caused by some new struct fields in any of its parameters.

// driver/event_table.c

const struct ppm_event_info g_event_info[PPM_EVENT_MAX] = {

// ...

/* PPME_SYSCALL_OPENAT2_E */ {

"openat2", EC_FILE, EF_CREATES_FD | EF_MODIFIES_STATE, 0

},

/* PPME_SYSCALL_OPENAT2_X */ {

"openat2", EC_FILE, EF_CREATES_FD | EF_MODIFIES_STATE, 6, {

{"fd", PT_FD, PF_DEC},

{"dirfd", PT_FD, PF_DEC},

{"name", PT_FSRELPATH, PF_NA, DIRFD_PARAM(1)},

{"flags", PT_FLAGS32, PF_HEX, file_flags},

{"mode", PT_UINT32, PF_OCT},

{"resolve", PT_FLAGS32, PF_HEX, openat2_flags}

}

},

}

The next step is to map the events to the fillers, which are the actual tracing code for the syscall that we will cover in the next sections. sys_empty is a simple stub for when we are not interested in having a specific trace, which suits our use case for the syscall enter event.

// driver/fillers_table.c

const struct ppm_event_entry g_ppm_events[PPM_EVENT_MAX] = {

// ...

[PPME_SYSCALL_OPENAT2_E] = {FILLER_REF(sys_empty)},

[PPME_SYSCALL_OPENAT2_X] = {FILLER_REF(sys_openat2_x)},

}

We also need to update FILLER_LIST_MAPPER with the filler for our exit event. This is just a simple X-macro that is used to automatically fill the enum ppm_filler_id and various filler functions declaration in the same header.

// driver/ppm_fillers.h

#define FILLER_LIST_MAPPER(FN) \

// ...

FN(sys_openat2_x) \

// ...

FN(terminate_filler)

// ...

Next, we will make sure to add the new syscall to both the syscall table and the routing table. g_syscall_table maps a syscall with some flags and its enter and exit events constants. We discovered the meaning of each flag by inspecting its definition and by looking at the way they were used in other parts of the code.

// driver/syscall_table.c

const struct syscall_evt_pair g_syscall_table[SYSCALL_TABLE_SIZE] = {

// ...

#ifdef __NR_openat2

[__NR_openat2 - SYSCALL_TABLE_ID0] = {

UF_USED, PPME_SYSCALL_OPENAT2_E, PPME_SYSCALL_OPENAT2_X

},

#endif

};

Then, the g_syscall_code_routing_table table maps the platform syscall number to our internal enumeration:

// driver/syscall_table.c

const enum ppm_syscall_code g_syscall_code_routing_table[SYSCALL_TABLE_SIZE] = {

// ...

#ifdef __NR_openat2

[__NR_openat2 - SYSCALL_TABLE_ID0] = PPM_SC_OPENAT2,

#endif

};

Be mindful that there are counterparts of g_syscall_code_routing_table and g_syscall_table for ia32. Please be sure of updating those too!

Fillers

Ok, we are finally nearing real kernel code! Fillers are functions that implement the specific capturing behavior for each event. There is a filler for each enter and exit event of the supported syscalls, wherever they are not stubbed by sys_empty. Fillers need to be implemented for both the kernel module and the eBPF probe separately.

The logic of filler functions is pretty straightforward. All they need to do is collect the return value and the arguments of a syscall, either at the enter or the exit event and then push that information in a ring buffer. Then, libscap takes care of consuming the data in the ring buffer from the userspace. The extraction of those values, and pushing to the ring buffer, is implemented by specific helper methods.

Kernel module

To write the kernel module filler function, let's head to driver/ppm_fillers.c where we can find lots of f_sys_ functions. We just need to write a new one using the same name that we previously added to driver/ppm_fillers.h. Our openat2 filler function for the exit event looks as follows:

// driver/ppm_fillers.c

int f_sys_openat2_x(struct event_filler_arguments *args)

{

// ...

return add_sentinel(args);

}

The first thing to do is setting the return value and pushing it to the ring buffer:

int64_t retval = (int64_t)syscall_get_return_value(current, args->regs);

int res = val_to_ring(args, retval, 0, false, 0);

if (unlikely(res != PPM_SUCCESS))

return res;

Then, we collect each argument and push it to the ring buffer. Be mindful that the order with which we push data on the ring buffer needs to be coherent with the one that is expected in the userspace by libscap and libsinsp.

syscall_get_arguments_deprecated(current, args->regs, 1, 1, &val);

res = val_to_ring(args, val, 0, true, 0);

if (unlikely(res != PPM_SUCCESS))

return res;

At this point, we had to decide whether to push the open_how struct argument in the ring right ahead or to flatten it and push all its fields one by one. We had good reasons to opt for the second option. First, due to the novelty of openat2 and its definitions, we wanted to isolate the usage of the data structure only at the kernel level to avoid compilation errors and make the build system more resilient. Second, the data structure may be not defined in userspace even if the kernel sees and compiles it, due to a potential mismatch between the glibc version and the installed kernel headers. Lastly, libscap and the components above are designed to be independent of the underlying OS, so it would have been inappropriate to deal with this detail at their level.

unsigned long flags = 0;

unsigned long mode = 0;

unsigned long resolve = 0;

#ifdef __NR_openat2

struct open_how how;

syscall_get_arguments_deprecated(current, args->regs, 2, 1, &val);

res = ppm_copy_from_user(&how, (void *)val, sizeof(struct open_how));

if (unlikely(res != 0))

return PPM_FAILURE_INVALID_USER_MEMORY;

flags = open_flags_to_scap(how.flags);

mode = open_modes_to_scap(how.flags, how.mode);

resolve = openat2_resolve_to_scap(how.resolve);

#endif

// ...

There are a few takeaways here:

- Flags are converted in the internal representation before being pushed in the ring. This means that

libscapexpects data to be already encoded with the internal definitions. - There is a conditional compilation for

__NR_openat2. This small trick allows compiling the filler on old kernels that did not support openat2 syscall by simply stubbing the argument values to zero. This is more a compilation concern because the syscall will obviously not be caught by old kernel versions in the first place. - When reading a pointer argument provided from the syscall caller, we need to copy the memory from userspace to kernel space, using

ppm_copy_from_user, before being able to access it.

eBPF probe

Implementing the filler for the eBPF probe is just a matter of changing the function signature we used in the kernel module to use the FILLER macro instead.

// driver/bpf/fillers.h

FILLER(sys_openat2_x, true)

{

// ...

return res;

}

The FILLER macro will declare an __bpf_sys_openat2_x inline function in the bpf section tracepoint/filler/<name>, that will be called from the sys_exit probe when the corresponding syscall gets intercepted. Please note that this redirection happens as an eBPF tail call. Details about the eBPF execution model are out of the scope of this post, but you can find some interesting resources here.

Then, the body of the eBPF filler is implemented as a faithful copy of what we already did in the kernel module, by just the helper methods involved:

syscall_get_return_value->bpf_syscall_get_retvalsyscall_get_arguments_deprecated->bpf_syscall_get_argumentval_to_ring->bpf_val_to_ringppm_copy_from_user->bpf_probe_read

At this point, even if you are lucky enough to compile all these changes on the first try, you can still expect the kernel to reject the newly produced eBPF probe. To guarantee its safety, the kernel has a verifier that checks the eBPF bytecode before actually launching it.

The technology is still at an early stage, and there is no explicit agreement between the clang compiler and the Linux kernel between the bytecode produced and the one accepted. Documentation on these aspects can be found on the web for further reference. The good news is that the filler functions are simple enough to avoid this kind of risk if implemented correctly.

Libscap

The only update that is required in libscap to support new syscalls is to add it in the records of g_syscall_info_table. This adds some context information on the syscall, that is used by libscap for its business logic.

// userspace/libscap/syscall_info_table.c

const struct ppm_syscall_desc g_syscall_info_table[PPM_SC_MAX] = {

// ...

/*PPM_SC_OPENAT2*/ { EC_FILE, (enum ppm_event_flags)(EF_NONE), "openat2" },

};

Libsinsp (optional)

Indeed, libsinsp is one of the most complex components of Falco. It is responsible for parsing and filtering events, formatting output alerts, and maintaining an internal state. The process of adding a new syscall inside libsinsp is quite harder than what we saw so far. More specifically, there are no specific points in the codebase in which new code or metatada must be inserted. Instead, we must figure out which areas of the libsinsp business logic are affected by the introduction of the new syscall.

In this perspective, we started by trying to answer some fundamental questions. Should the syscall event be parsed in a specific way? Does the syscall introduce new event fields that we want to support in the filtering syntax? Must the syscall argument data be fetched, or retrieved, in a non-standard way? Does the syscall event alter the internal state or the cached values? None of these questions are easy to be addressed without some broad knowledge of the codebase of libsinsp. Accordingly, we proceeded by looking at some code areas that could be relevant for our purposes.

At a high level, the core job of libsinsp is to receive an event from libscap and then perform tasks related to parsing and filtering. Here, parsing means inspecting the event information, triggering internal state or cache changes, adding context metadata to the event, and calling some listener callbacks. Instead, the filtering part refers to the task of evaluating a boolean expression with the given event, to decide whether to discard it or not. Spoiler alert, it was not a surprise to discover that most of the business logic was dependent on the type of event and system call and that libsisnp processes each of them, case by case, with switch statements.

For context, the logic filters accepted by libsinsp look like the following:

proc.name!=cat and evt.type=open

This is a simple boolean expression, in which each term is an assertion between a field extracted from the event and an expected value. The supported operators can be found here: https://falco.org/docs/rules/conditions/#operators.

Parsing

We started by looking at the sinsp_evt class that represents system events in the type hierarchy of libsinsp, which is a simple data container enriched by an extensive set of accessor methods.

// userspace/libsinsp/event.cpp

class SINSP_PUBLIC sinsp_evt : public gen_event

{

public:

uint64_t get_ts();

uint16_t get_source();

uint16_t get_type();

// ...

};

In that, we noticed the presence of some predicative getters for file-related operations, to which we suspected openat2 to be related. For reference, we updated the following method sinsp_evt::is_file_open_error. Notably, we had a strong hint on this method due to the presence of the openat constants inside the check. As such, we just appended the constants of openat2 inside the if statement.

Observe that mimicking the way other already supported syscalls are processed is a good way of figuring out how to add new ones, and we used this trick extensively to understand the way libsinsp works.

bool sinsp_evt::is_file_open_error() const

{

return (m_fdinfo == nullptr) &&

((m_pevt->type == PPME_SYSCALL_OPEN_X) ||

// ...

(m_pevt->type == PPME_SYSCALL_OPENAT_X) ||

(m_pevt->type == PPME_SYSCALL_OPENAT2_X));

}

Then, inside the sinsp_parser::process_event method we noticed a pretty big switch statement over most of the supported event types. This method executes specific tasks for each different syscall and simplifies its job by grouping them into categories. In our case, we added our PPME_SYSCALL_OPENAT_2_X constant to fall in the sinsp_parser::parse_open_openat_creat_exit method (the constants for openat were already there). Since we also implemented our exit filler to be very similar to the one of openat, adding the PPME_SYSCALL_OPENAT2_X constant in a few if statements were enough to include our new syscall in the parsing flow. The source code of our pull request is pretty self-explanatory from this perspective.

Filtering

We start by giving a quick intro of how libsinsp filters the captured events. In the library, the filtering feature is implemented through the filter_check hierarchy. Instances of this class represent the terms of the user-specified boolean formulas to perform the actual checking. filter_checks are modeled to perform a single check over a single event field. The complete list of the supported event fields is visible by running Falco with the --l option. The sinsp_filter_check class is at the root of the hierarchy:

class sinsp_filter_check : public gen_event_filter_check

{

public:

// ...

virtual bool compare(sinsp_evt *evt);

virtual uint8_t* extract(sinsp_evt *evt,

OUT uint32_t* len, bool sanitize_strings = true) = 0;

// ...

};

Each child class of sinsp_filter_check represents one of the categories of event fields supported in Falco, such as fd.*, process.*, evt.*, and all the rest. The most relevant methods are compare and extract. The first is responsible for performing the actual field check, whereas the latter helps retrieve the field value in case it is not already present either in the event object or in the engine state.

As such, we have to figure out which filter_check we need to update with our new syscall. Again, following what was already done for openat was truly helpful. Long story made short, we had to update the extract methods of the sinsp_filter_check_fd and sinsp_filter_check_event. We also updated a string inside the sinsp_filter_check_event_fields table, which is where all the text information printed through the Falco --l option comes from.

Testing

At this point, we were sure to have written all the code required to support the openat2 syscall, but unfortunately, the work was far from being finished.

One of the first obstacles was compiling the source code over different versions of the Linux kernel and the compilers. We fixed our compilation issues through the aforementioned use of #ifdef statements in the kernel drivers and libscap, which made the build setup more robust. The openat2 syscall, and all the metadata related to it, are simply ignored if the underlying kernel version can't support it.

Another challenge was testing our work and verifying that Falco was able to monitor the new syscall. For this purpose, we wrote a small program making use of openat2. Something like the following snippet will suffice to do the testing for other syscalls too.

int main(int argc, char** argv)

{

const char* pathname = "/tmp/openat2_test.bin";

struct open_how how;

how.flags = O_CREAT | O_RDWR;

how.mode = 07777;

how.resolve = RESOLVE_BENEATH | RESOLVE_NO_MAGICLINKS;

int res = syscall(SYS_openat2, AT_FDCWD,

pathname, &how, sizeof(struct open_how));

if(res == -1)

perror("Could not call openat2");

else

printf("Result: %d\n", res);

return 0;

}

The testing setup is fairly simple. First, we had to compile Falco with the new version of libs, and we ran it with an ad-hoc ruleset that we were sure would trigger some alerts once our sample program was running. A rule filter such as evt.type=openat2 will suffice. Then, we ran the little program above and checked that Falco effectively sent some output alert (luckily, it did).

Whoever reproduces the same experiment must be mindful of testing it with both the kernel module and the eBPF probe to assert that the feature parity guarantee of the two drivers gets respected.

Conclusion

Honestly, we had tons of fun while working on this project. But this is just the beginning, as there are still plenty of syscalls to work on. Adding support to new system calls is always one of the best ways of contributing to Falco for three good reasons:

- The monitoring capabilities of Falco increase with every new syscall it supports, and it becomes progressively harder to bypass its control.

- Supporting new syscalls requires the exploration of the whole stack of components that are part of Falco. This is a sublime way to quickly learn about the project and its inner structure.

- It's a fast and good way to contribute to a top-quality open source project and its community.

You can find us in the Falco community. Please feel free to reach out to us for any questions, suggestions, or even for a friendly chat!

If you would like to find out more about Falco:

- Get started in Falco.org

- Check out the Falco project in GitHub.

- Get involved in the Falco community.

- Meet the maintainers on the Falco Slack.

- Follow @falco_org on Twitter.